Christmas at the Front: A Leicestershire Perspective

24 December 2014

The well-known and illustrated Christmas Truce of 1914 is often considered a unique occurrence within the violence of The Great War. It has been represented in some books and dramatisations as a total cease-fire on Christmas Day, 1914. For many years the only tangible representation of the 1914 truce was a wooden cross, placed in 1999 by the Khaki Chums close to Ploegsteert Wood – or Plugstreet as it was known by the British Tommies. On the 4th December 2014 the Belgian people at Messines unveiled a permanent memorial.

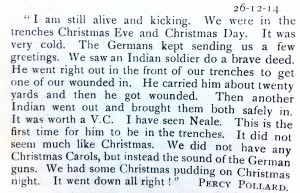

From research into local representation in the Great War, I found a letter in the village of Syston’s Parish Magazine from a Leicestershire soldier, Percy Pollard, dated 26th December 1914.

These few lines reveal that all was not quiet along the entire Western Front at Christmas 1914. The legend that a game of football was played between opposing troops is also a matter of conjecture.[1]

However, Christmas 1914 is not the only recorded suspension of hostilities during the First World War and a second brief cease-fire may have followed in 1915, but is far less renowned, partly because any fraternisation was strongly discouraged by the military authorities on both sides.

The short extract that follows is taken from a paper I presented at an International First World War Conference: ‘Perspectives on the Great War’ at Queen Mary, University of London on 4th August 2014. The paper was prepared using documents that had been deposited at the Leicestershire and Rutland Records office by the relatives of Captain Charles Aubrey Babington Elliott, OBE, JP, of the 8th Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment during the First World War, and Lieutenant-Colonel in the Second.[2] A particularly interesting part of these documents is the correspondence between ‘Cabbie’ Elliott and the German soldier and controversial author, Ernst Jünger.

The paper considers if a possible second Christmas Truce in 1915 was indeed fact or fabrication.

Documentation of such an event only came to wider attention in 1920 with the publication of Ernst Jünger’s In Stahlgewittern, translated into English in 1929 as Storm of Steel.[3]

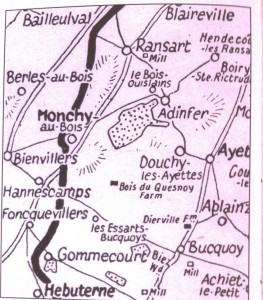

Ernst Jünger was a lieutenant in the 73rd Hanoverian Fusiliers and had been entrenched at Berles-au-Bois, when he took part in an exchange with British soldiers.

Serving with the Leicestershire Regiment in the same area was Captain Charles Elliott who, like Jünger, kept pocket diaries and from these he was able to compare Jünger’s accounts in Storm of Steel with those of his own. On the 19th December 1929, after compiling five pages of notes, Captain Elliott wrote from his home in Oadby, to Ernst Jünger:

‘Dear Mr Jünger,’

‘I have just been reading your Storm of Steel and find that for many months we lived within a few hundred yards of each other. We always heard that you had stopped at Monchy-au-Bois. Was that true?’

Ernst Jünger replied to the letter on the 30th December 1929, from his home in Berlin:

‘Much esteemed Mr Elliott,’

‘Your kind letter gave me great pleasure, for it is curious enough, after such a long time, to receive intimate particulars from a former enemy, whom one scarcely knew, although one lay barely one hundred metres from him. I came only to Monchy at the end of 1915, but I know that at the close of 1914 there was hard fighting round the village.’

Captain Elliott compared his diary with the novel:

‘On referring to the loyal diary I kept, and comparing it with your book, I found many interesting sentences and our stories regarding weather conditions are almost the same.’

He quotes from Storm of Steel, for 30th October 1915:

‘Owing to heavy rain in the night, the trench fell in in many places, and the soil mixing with the rain to a sticky soup turned the trench into an almost impassable swamp. The only comfort was that the English were no better off, for they could be seen busily scooping water out of their trench.’

The weather dominated the writing of both men for quite sometime, speaking of flooded dugouts and a roof dripping like a watering can.

In Storm of Steel Jünger recounts his surprise when on the 12th December he left a shelter he had been staying in:

‘I couldn’t believe the sight that met my eyes. The battlefield that previously had borne the stamp of deathly emptiness upon it was now as animated as a fairground. The throng of khaki-clad figures emerging from the hitherto so apparently deserted English lines seemed as eerie as the appearance of a ghost in daylight.’

He also describes a lively exchange of schnapps, cigarettes and uniform buttons.[4]

The surreal harmony suddenly disintegrated; a shot rang out and a German soldier lay dead. Jünger tells of both sides scurrying back to their trenches whereupon he called out that he wanted to speak with an officer. Several British soldiers went back and later returned with ‘a young man from their firing trench with a somewhat more ornate cap.’ For ease of exchange, they spoke in French. Ernst Jünger castigated the officer for such a deceitful shot. The Officer said it was from the rifle of a soldier in a different Company and not his. When shots hit the ground close to him, the British Officer called out:

‘Il y a des cochons aussi chez vous!’[5]

Jünger wrote that he would have liked to have exchanged souvenirs, but the two men had agreed that war would recommence three minutes after their negotiations ceased. After the talks ended, the German artillery began firing, but once again Jünger was astounded. Stretchers were being carried by the British into the open ground and all firing ceased once more. Jünger wrote that he was very proud of his troops. He said: ‘The Commandant, Colonel Von Oppen, did not approve of our fraternising, but I thought it great fun.’

Jünger’s writing also identifies the British regiment involved in this sportsmanlike exchange. In chapter 5, Trench Warfare, Day-by-Day he wrote:

‘From the British cap-badges seen that day, we were able to tell that the regiment facing ours were the Hindustani Leicestershires.’[6]

Hindoostan was super-scribed on the cap badge in recognition of the Regiment’s commendable conduct whilst serving in India between 1804 and 1823.

As Christmas approached the weather worsened and according to Jünger’s diary for 23rd December 1915:

‘Mud and filth are getting the better of us. This morning at three o’clock an enormous deposit came down at the entrance to my dugout. I had to employ three men, who were barely able to bale the water that poured like a freshet into my dugout. Our trench is drowning, the morass is now up to our navels, it’s desperate. On the right edge of our frontage another corpse has begun to appear, so far just the legs.’[7]

Christmas Eve 1915:

‘We spent Christmas Eve in the line, and, standing in the mud, sang hymns, to which the British responded with machine-gun fire.’ The War Diary suggests it was sniper fire.

On Christmas Day Jünger wrote:

‘We lost one man to a ricochet in the head. Immediately afterwards the British attempted a friendly gesture by hauling a Christmas tree up on their traverse, but our angry troops quickly shot it down again, to which Tommy replied with rifle grenades.[8] It was all in all a less than merry Christmas.’

Whilst there is some discontent with Ernst Jünger’s account, and perhaps what happened in December 1915 cannot be considered an accomplished truce but a series of fraternisations, this account is about a fellowship and has culminated in two opposing officers being able to find a personal truce through the written word.

Karen Ette, August 2014,

This abridged version December 2014.

References:

[1] Chris Baker, The Truce: The Day The War Stopped (Stroud: Amberley, 2014)

[2] Matthew Richardson, Fighting Tigers: Epic Actions of the Royal Leicestershire Regiment (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2002), p. 85.

[3] Ernst Jünger, Storm of Steel (London: Penguin, 2004)

[4] Jünger, p. 57.

[5] ‘There are some swine on your side too!’ Jünger, Storm of Steel, p. 57.

[6] Jünger, p. 58.

[7] Jünger, p. 58

[8] Jünger, p. 58-59. The War Diary confirms that rifle grenades were fired by the Leicestershire Regiment.