Fearon Fountain unveiled

31 August 2020

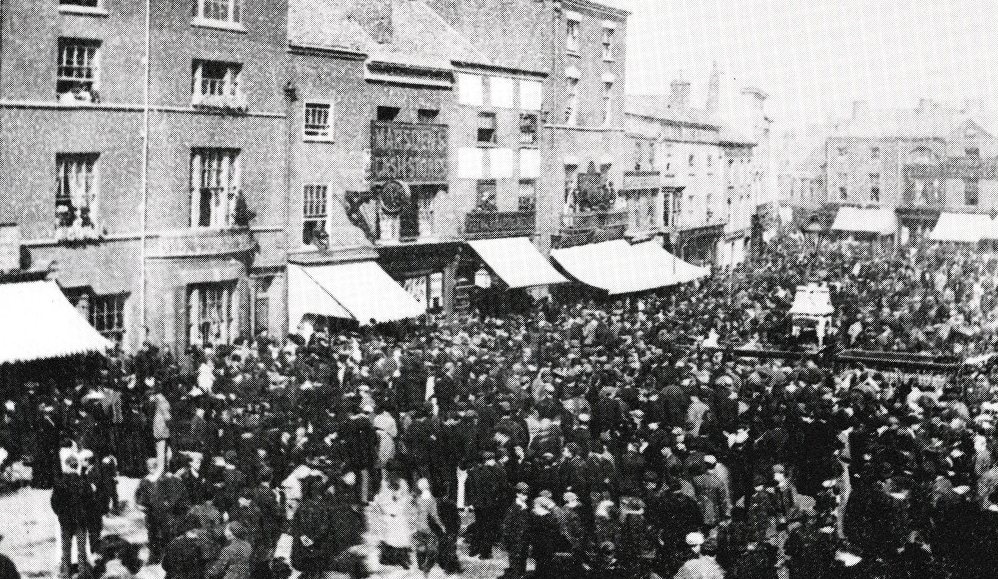

Loughborough’s iconic drinking fountain was unveiled in the Market Place on 31st August 1870 by Archdeacon Henry Fearon, who presented it to the town to mark the arrival of its long-awaited public water supply on the completion of the Nanpantan Reservoir.

The fountain was made for Fearon by James and William Forsyth, brothers from Scotland with extensive experience of creating monuments for clients across the country. It’s built in a simple rustic style, with a base of Ashlar (finely-dressed stone) and four columns of polished Aberdeen granite, each topped with carved foilage. On top of these sit four arches and a canopy on which are carved the year of unveiling and a coat of arms. A cast iron lamp caps the structure.

Carved lions’ heads adorn two sides of the fountain, with polished marble basins to the remaining sides. Metal cups on chains were originally fixed beside the basins.

An inscription is spaced around the four sides of the fountain: ‘our common mercies – loudly call – for praise to God – who gave them all.’

Brass plaques are now set into the pavers around the base of the fountain, a modern addition commemorating the towns’ partnership with communities across the world.

The fountain has a Grade II listing and was restored in 1981, when it was raised slightly higher by the addition of a plain plinth. Unfortunately it doesn’t currently dispense water.

A huge crowd gathered to see Archdeacon Fearon dedicate the fountain back in 1870, and to watch him drink the first cup of water from it.

Alison Mott

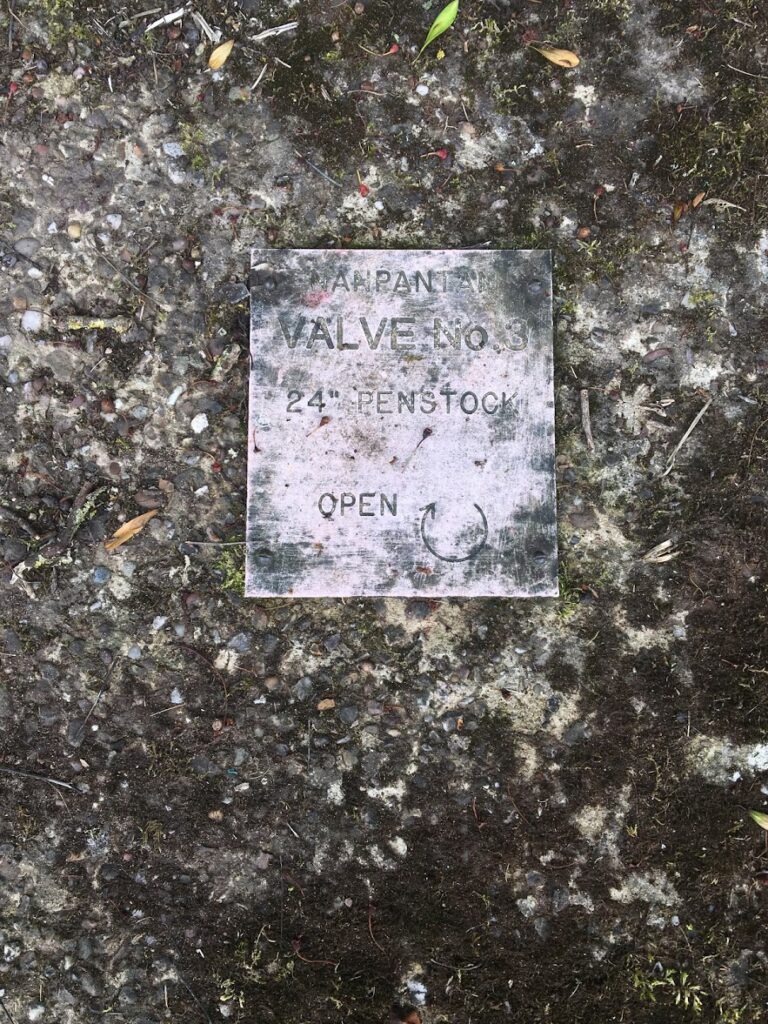

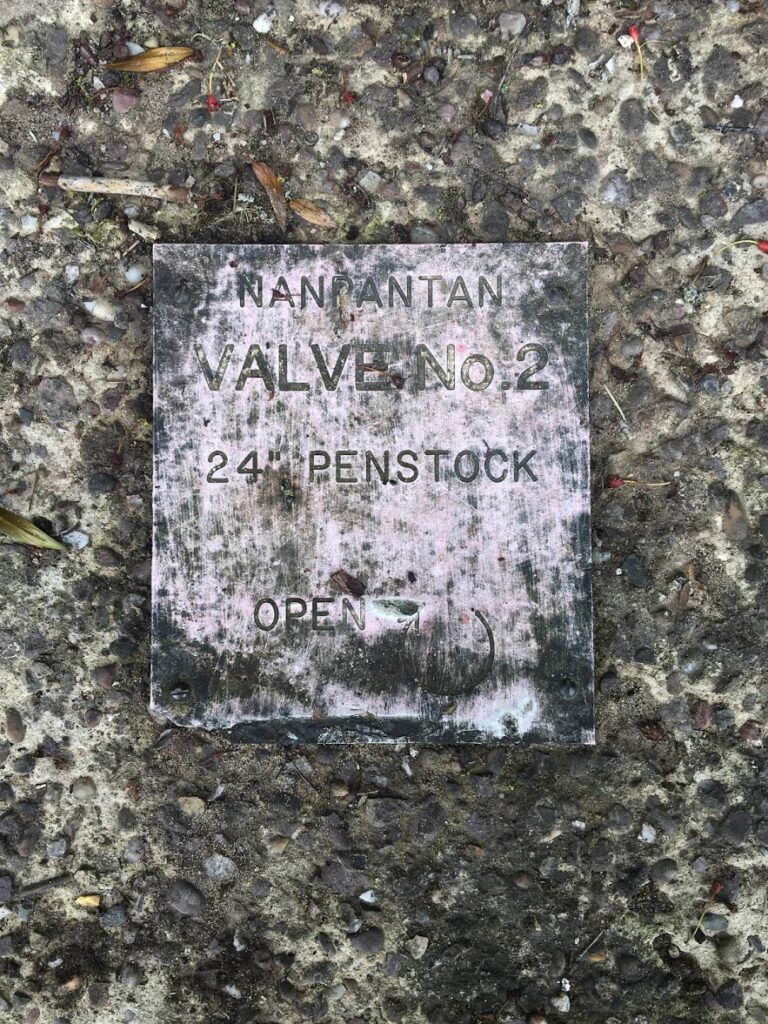

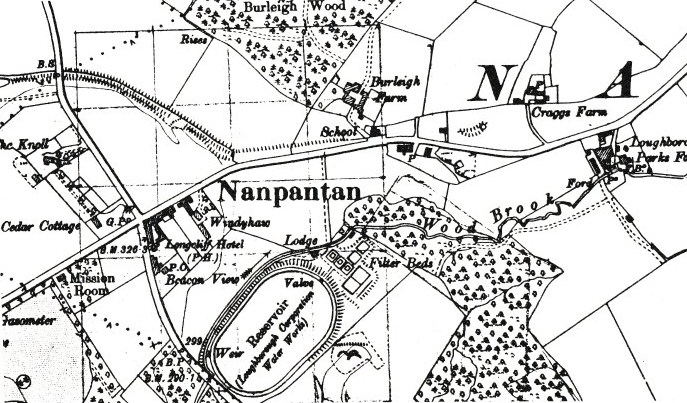

Nanpantan Reservoir 2020

31 August 2020

Nanpantan Reservoir was built to supply filtered water to Loughborough following recommendations made in 1849 by the government’s General Health Board Inspector, William Lee. Lee was called to evaluate the town’s water and sewage systems because of high local mortality rates and repeated outbreaks of cholera.

The reservoir holds 29 million gallons of water on its 8¾ acre-site and it and it’s treatment system cost £23,500 to build. It was opened in 1870.

These photos were taken during ‘permitted daily exercise’ in Lockdown 2020 during another pandemic, this time for Cov-19.

Photos © Alison Mott – May 2020

Nanpantan Reservoir 1870

31 August 2020

‘Four different engineers had given reports upon this question, dealing with the watershed of the Woodbrook at Nanpantan, and the Blackbrook near Onebarrow Lodge. Eventually the former was selected, a reservoir and filter beds with capacity of 29 million gallons 8 ¾ acres in extent, and the town supplied from this source by natural gravitation.’

‘These were opened in 1870 at a cost of £23,500 by Archdeacon Fearon who, in commemoration thereof erected the water drinking fountain in Market-place.’

‘What a boon this water supply was to the town can easily be imagined, in comparison with the existing foul-smelling wells polluted by sewage and filth from the street.’

Joseph Deakin in ‘Loughborough in the XIXth Century’ (Pub. Echo Press Limited).

Images from ‘Bygone Loughborough in Old Photographs Vol 2.’

See what Nanpantan Reservoir looks like in 2020 here.

Post by Alison Mott

Rev Fearon speaks at Health Board Inquiry

30 August 2020

In July 1849 – just over a year after Henry Fearon became Rector of All Saints Parish – an inspector was sent by the General Board of Health in London to assess the sanitary conditions in Loughborough. His name was William Lee (1778-1863), a man with extensive experience in the field who led similar enquiries right across the country, including in Leicester in 1852.

Lee discovered that the town’s cleanliness was the responsibility of the Board of Surveyors – a 12-man committee of locals – mostly unpaid – who met once a month in the Mundy Arms to organise cleaning and repairing the town’s roads and the clearing-away of public ‘nuisances’ – a nineteenth-century term for filth and waste. It was obviously a system that wasn’t working well and the picture Lee gathered of mortality, disease and lack of sanitation in the town was grim.

He toured the town for himself, asking questions about what he saw and looking into buildings and behind structures. He had wells uncovered and street furniture moved. In one place, yards from a business and close to dwellings, Lee found a wooden cover on the ground which no one could explain. Lee had it lifted, to find ‘a large cistern full of putrid water, which smelt […] as bad as a cesspool.’ He recorded that ‘the occupant of the adjoining house had had four children ill of the fever, and one had died.’

As well as site visits, Lee called people in for interview, including several who’d been unwell, as well as a doctor, William Grimes Palmer, who provided healthcare to the poor.

Lee noted the townsfolk had ‘a depressed, cadaverous look – the lips […] almost white – the veins blue’ and they appeared ‘prematurely aged.’ People complained of ‘pains in the head, stomach and the left side, loss of appetite and strength, nervous irritability, cold sweating, of frequent fainting in all bad cases, and numerous instances of almost continuous diarrhoea.’

Dr Palmer felt compelled to mention Chapman’s Yard in Baxter Gate, which he thought he’d been called to visit ‘more frequently than into any other.’ It had no drainage, being until recently ‘an open cesspool,’ though now covered over. The houses were dirty and badly aired, with no back exits and no means, therefore, of through-ventilation. Worse still, a piggery stood at the top of the yard from which sewage overflowed into it. ‘I do not know a worse yard in the town than that,’ Palmer stated. ‘There has scarcely been a house [there] free from fever, at first of a mild, low character, but running into the typhoid state.’

Henry Fearon also spoke at the inquiry, drawing on his expert knowledge of sanitary science and speaking eloquently and extensively about the general condition of the poor, much of which was beyond the remit of the Board.

Many of his parishioners spent all day sitting at their work, he said, particularly women and girls doing ‘finishing’ work for the stocking, shirt, glove and cap making trades. They worked indoors and should have ‘a pure air to breathe’ when they opened their windows, which ‘I cannot say they have generally.’

It wasn’t uncommon for busy working families to keep young children quiet with ‘medicines’ containing laudanum (opium), to which they often became addicted. Henry Fearon was sad to see ‘affectionate mothers who would die to protect their offspring’ forced to destroy them instead, for even if they survived infancy, they’d grow up ‘enfeebled and […] predisposed to disease.’

William Lee pulled his findings together into a 55-page report for the General Board of Health. It ended with a three-page list of recommendations for the town’s administrators to action. The first thing they needed to do was to set up a Local Board of Health – whether the ratepayers wanted one or not.

Alison Mott

Read the last post in the topic thread here.

Read the next post here.

Loughborough’s Health in 1848

29 August 2020

The industrial revolution caused towns such as Loughborough to grow rapidly as the newly-established factories drew unemployed craftsmen and women away from their homes in the countryside and into the towns to operate the machinery that was replacing their skills.

This influx of people quickly created overcrowding. The sale of pockets of town-land by the Earl of Moira in the early eighteen-hundreds caused a building boom in Loughborough, infilling veg plots and orchards, yards and alleyways with custom-made buildings, and helping fulfil the need for more and more homes and commercial premises.

The town became packed with little courtyards of dwellings wedged between businesses. Slaughterhouses stood next to cottages, tanneries beside shops, farmyards shared yards with engineering sheds. Human, animal and industrial waste ran off into cesspools next to wells where families drew water for cooking, bathing, cleaning and laundry. People lived cheek by jowl in hastily thrown together housing with poor ventilation, shared amenities, and little room to move.

Unsurprisingly, mortality rates soared, especially among the poor, as disease spread through this new urban environment.

In 1849 one in five of all children died before they were one year old, irrespective of their class. The average age of death across the population was 23 years 11 months, though this rose to the heady age of 55 years 9 months for those who managed to make it past twenty.

The mortality rate in Loughborough was 28 deaths per every thousand inhabitants (compared to 9.6 per thousand in 1983 and roughly 5.5 per thousand in 2006 for the Borough of Charnwood.)

Public health and sanitation was a national problem, discussed by princes and the aristocracy, the government and ordinary people on the street. A new cholera epidemic sweeping Europe prompted urgent need for reform.

The result was the Public Health Act of 1848, which received royal approval (thereby becoming an Act of Parliament) on 31 August 1848. The Act made recommendations developed from a report by Edwin Chadwick on the sanitary conditions of the labouring population of Great Britain.

The Public Health Act established a national General Board of Health, responsible for advising on disease prevention and with the power to set up Local Boards of Health where needed, to take over and formalise work previously done in parishes by charities and voluntary bodies. The idea for these Local Health Boards wasn’t universally popular, however, largely because of concerns they’d incur costs that would raise local tax rates.

Areas could petition to have a Local Board of Health, requiring ten percent of the ratepayers to sign the request, or the General Board could force a Local Board upon an unincorporated town judged to need one from high local death rates (the benchmark being an average mortality rate of 23 out of 1000 people over the previous 7 years).

Loughborough was one of the towns to petition the General Board of Health, with two hundred local ratepayers signing the request (though interestingly, only one of the town’s doctors). The petition was irrelevant, however, given the high death rate in the town. Loughborough was on the radar of the General Board of Health and the way things had been managed pretty much since medieval times was about to change.

Alison Mott

Read the previous post in the thread here.

Read the next post about this topic here.

What has Henry Fearon ever done for us?

28 August 2020

Every time you draw a glass of water from a tap in Loughborough, spare a thought for Reverend – later Archdeacon – Henry Fearon, without whose cunning and determination that everyday action (which we so readily take for granted) might not have come about.

‘But he lived long before I was born,’ you might say, ‘so what’s he got to do with me?’ To answer that question properly, we need to go right back to the beginning of Henry Fearon’s story – or at least, to the time he first arrived in the town.

We begin the tale in 1848.

The Reverend Henry Fearon (1802-1885) was granted the living of Loughborough All Saints Parish on 14th February 1848 and officially took up post as Rector on 3rd of May the same year, shortly before his 46th birthday. A graduate of Cambridge University, he’d spent some of his time there studying ‘sanitary science’ – one of the hot topics of the day, followed avidly by the Queen’s Consort, Prince Albert, who despaired at the situation of the British labouring classes and was encouraging the building of new homes with good ventilation and decent sanitation for them to live in.

These matters were debated in newspapers and periodicals and presented to the fiction-loving public by celebrated authors such as Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell and Charles Kingsley, to name but a few. It wasn’t uncommon for the middle- and upper-classes to visit slums to see the situation of the poor first hand – as did Dickens himself, touring areas of London with Dr Thomas Southwood Smith, who’d worked on the 1834 amendment to the Poor Law under the leadership of social reformer Edwin Chadwick.

Unaware as yet that infection and disease are transmitted by bacteria, it was believed then that illness was carried by smell. The wealthy therefore viewed poor health and shortened life expectancy as the predicament of the unwashed poor and it was generally believed that improving sanitation was key to addressing the social issues of the lower classes.

And to an extent, they had a point. Overwork, overcrowding, poor diet and poor physical health made the working population susceptible to the outbreaks of typhus, cholera, and smallpox which regularly spread across the country.

By 1848 poor sanitation and its affects on the poor had been debated for well over a decade. Henry Fearon arrived just before a small outbreak of cholera in Loughborough and just as the debate about sanitation was to step up a gear in the town.

Alison Mott

Read the next post in this topic here.

150 years of the Fearon Fountain

28 August 2020

This weekend sees the 150th anniversary of the unveiling of the Fearon Fountain in Loughborough Market Place.

To mark the occasion, we’re sharing the story of Archdeacon Henry Fearon and his connection to the campaign to bring fresh water to Loughborough. Fearon himself commemorated the success of the campaign by paying for the installation of the water fountain in the centre of town and drawing the first cup of water from it on 31st August 1870.

Join us each day this weekend as we share a piece of the story. And if you’re in town, pop by and look at the fountain. It’s not looking too bad for a hundred-and fifty-year-old!

Photo © Alison Mott

Read the first part of the story here.

Boy Killed by a Lion in Loughborough

21 August 2020

Tudor England was a dangerous place. There were plagues and wars, perilous childbirths and shocking infant mortality. Many risks were faced by people as they went about their everyday lives but what follows must have been a strange fate even in those days.

“Roger Sheppard, sonne in lawe to Nicholas Wollandes was sleayne by a Lyones – whiche was brought, into the towne, to be seyne of such as would gyve money to see her. He was soore wounded in sondrey places and was buried the xxi daye of august 1579.”

Source: The Record Office for Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland

A “sonne in lawe” in those days would have been a stepson and, at the time of the accident, Roger was only five years old. According to reports he received five wounds. The fatal wound was one in his left side, opposite his heart. It was one inch long, one inch wide and six inches deep. The accident happened at 11.00am on 20th August 1579 and Roger was buried the next day in the churchyard of Loughborough Parish Church. It was reported in the first parish record book.

The lioness was being looked after by John Castle in a room belonging to Nicholas Wollandes, a Bailiff of the town. It was chained to a beam. Clearly this was not enough to hold the animal back for the lioness was able to use its teeth and claws on its unfortunate victim.

Article written by the Loughborough Library Local Studies Volunteers.

References:

Dyer, Lynne (2017). Bridges, buses, trains, balloons and runners! Available here [Accessed 10 September 2017]

University of Oxford, Everyday Life and Fatal Hazard in 16th Century England.

Burleigh Park in 1881

15 August 2020

In his ‘Historical Handbook to Loughborough,’ published in 1881 by Loughborough printers H Wills, the Rev W G Dimock Fletcher shares the history of Burleigh Park, an estate on the edge of Loughborough now owned by Loughborough University.

‘Burleigh, or Burley, in the township of Loughborough, is probably derived from beorh or burh, a hill and lege, meadow land, signifying ‘the meadowland on the hill.’

‘Burleigh Hall is situated on a delightful eminence to the left of the road from Loughborough to Ashby, and there are about 375 acres of land, including the Park.’

‘Of the early history of Burleigh I can find no trace, but prior to 1485 the office of Keeper of the Park was granted to John Lee.’

‘In 1564 one family resided here. Leyland speaks of the Park as being a little way off from Loughborough, in tail mail[1]; and in 1569 the reversion was granted to Henry, Earl of Huntingdon, in tale mail, and in 1576 to him in fee[2]. In 1573 it had been assigned to Joan, widow of Sir Edward Hastings, for her dower.’

‘In 1626 Queen Henrietta Maria was granted an annuity of £115 16s 6d issuing out of the Manor of Loughborough and Burley. In 1630, John Davenport, Esquire lived here. In 1655 the Park was conveyed by Ferdinando, Earl of Huntingdon to William Rawlins.’

‘In the following year it was offered for sale, the Hall having been then recently built at a cost of £2600. The price asked was £11,767 16s. Sir William Jesson, Knight, then lived there.’

‘In 1711, Henry Tate, Esquire, High Sheriff of the County, was living here, and in this family it has continued ever since, Colonel Tynte being the present owner. Until lately it was occupied by Charles Sutton, Esquire, and now by the Dowager Lady Herries. The Hall is a capital three storied house, to which an avenue and fine old trees leads up. The neighbourhood is delightful, and there is a fine view of Charnwood Forest from the Hall.’

[1] passed down through the male ancestral line

[2] A trust or settlement in common law which restricts who may inherit an estate. See further here.

Loughborough Grammar and Commercial School

9 August 2020

‘Then came a momentous day in the history of the town when, on August 9th 1850 the Lord Bishop of Peterborough, George Davys, D.D., returned to his native town to lay the foundation stone of the new Grammar and Commercial School in what is now the Burton Walks, which was to replace the old Free School he had attended.

The day was made a general holiday, the bells in the Parish Church rang and, we are told, there was a “feeling of universal gladness and goodwill.”

Children were each given a penny bun. There were flags everywhere and a triumphal arch was erected at the entrance of Mr. Warner’s Park (the Elm’s Park), where a large number sat down to tea. A greasy pole and fireworks rounded off the entertainment.’

From ‘19th Century Loughborough’ by W. A. Deakin, The Echo Press Limited, 1974