Loughborough Parish Library (5): A What-if Story from Loughborough’s Old Rectory

3 August 2024

In this article, Ursula Ackrill discusses the book-collecting habits of the clergyman who became Rector of Loughborough Parish on the death of James Bickham, and the ‘degrees of separation’ which link that clergyman to one of the most famous literary figures of all time.

The Reverend Samuel Blackall (1737-1792) succeeded to the rectory of Loughborough in 1786. Upon arrival in his new home, he found a collection of books waiting for him which his predecessor – the Reverend James Bickham – had bequeathed in his will to his successors in perpetuity: 700 volumes overall. A fine collection, which Blackall may have appreciated more had he not brought with him a library of his own. He was 49, unmarried, fond of the families of his siblings. In his will he left his own library to his two favourite nephews, Samuel Blackall, a clergyman, and John Blackall, a medic.

Blackall managed to keep his books separate from the Parish Library so that they could stay in his family. However, at least three books from Blackall’s library were left behind after his death. They are in the current Loughborough Parish Library, which is deposited in Manuscripts and Special Collections at the University of Nottingham.

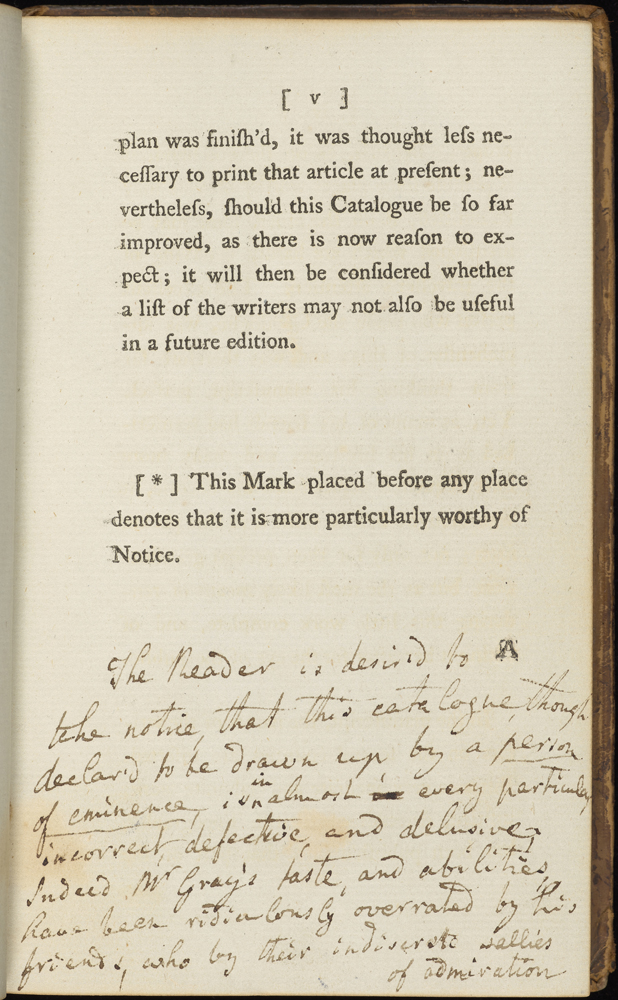

Blackall’s marginalia[1] show tantalising glints of his personality. In one instance, he could not resist puncturing what he perceived as a ‘cult of personality’[2] surrounding the poet Thomas Gray, whom his predecessor James Bickham had befriended in college.

Samuel Blackall comments in A catalogue of the antiquities, houses, parks, plantations, scenes, and situations in England and Wales by Thomas Gray (1773). Loughborough Parish Library, DA620.G73

When Samuel Blackall died in 1792, his nephew and namesake Samuel was 21. He had graduated from Emmanuel College, Cambridge, in 1791 and would become a Fellow of that college in 1794. He remained in college for twenty years. Presumably some or all of the library which the uncle had kept in Loughborough moved into his rooms there.

Emmanuel was both the uncle’s and the nephew’s alma mater. This raises the question why the nephew did not succeed the uncle to the rectory of Loughborough, which was within the college’s gift to bestow. The timing would have been perfect.

We know from contemporary sources, among them a lady with whom Blackall was briefly acquainted and nearly engaged to in 1798, that he was waiting patiently for one of the richest livings in the country to become vacant. That parish was North Cadbury in Somersetshire. In 1798, the lady’s hopes were disappointed. Fellows of Colleges were forbidden to marry, and Blackall must have felt unable to pursue a relationship at that point, knowing that the prospect of North Cadbury becoming vacant was a distant one.

Samuel Blackall became Rector at St Michael, North Cadbury, in 1812, when he was 42. In January 1813, newspapers printed the announcement of Samuel Blackall’s marriage to “Susanna Lewis, eldest daughter of James Lewis Esq. of Clifton, late of Jamaica”. The bride was the Jamaican-born daughter of a prosperous owner of a slave-run sugar plantation. Her dowry explains the speed with which the couple managed to build their new home. It was completed in one year and looked interesting enough for William Phelps to comment on it in Antiquities of Somersetshire. Phelps wrote in the tradition of the great historians and aesthetes of English country style, Robert Thoroton, John Throsby and John Nichols.

“The rectory house is a neat building, standing in a spacious lawn near the church, and was erected by the Rev. Samuel Blackall in 1813.”

This must also have been the next home of the library which Blackhall inherited from Loughborough. Just one year later, in 1814, the couple baptised their first-born, a daughter, and named her Elizabeth – possibly after a spirited heroine in an en vogue novel which had been published in 1813 called Pride and Prejudice. In any case, the family kept the name, as Elizabeth’s own first surviving child, a daughter, would be called Elizabeth also.

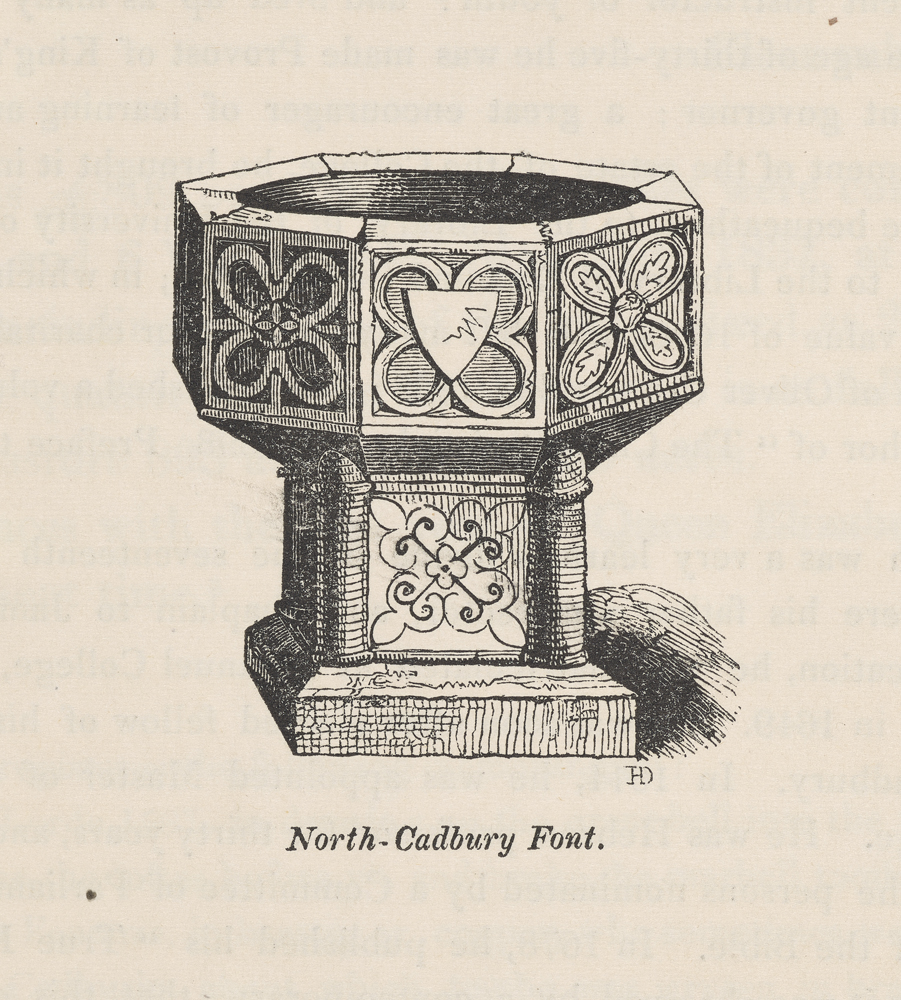

As an adult, the latter settled in Sudbury, Derbyshire, and died in 1892. It is possible, then, that books from Blackall the uncle’s Loughborough library survive somewhere in Derbyshire. Blackall’s rectory in North Cadbury no longer stands and our attempts to find an image of it proved fruitless. We have, however, an image of the baptismal font, in which Samuel Blackall’s daughter Elizabeth was baptised in 1814.

If Samuel Blackall had succeeded his uncle as rector of All Saints, Loughborough, the lady he met in 1789 may have been his bride and relocated to Loughborough’s Old Rectory. We know she felt jilted, because she wrote a letter to her brother which leaves us in no doubt about it.

“I wonder whether you happened to see Mr Blackall’s marriage in the Papers last Jan[uary]. We did. He was mar- ried at Clifton to a Miss Lewis, whose Father had been late of Antigua. I should very much like to know what sort of a woman she is. He was a piece of Perfection, noisy Perfection himself which I always recollect with regard. – We had noticed a few months before his suc-ceeding to a College Living, the very Living which we remembered his talking of & wishing for, an exceeding good one, Great Cadbury in So-mersetshire. –

I would wish Miss Lewis to be of a silent turn & rather ignorant, but naturally intelligent & wishing to learn; – fond of cold veal pies, green tea in the afternoon, & a green window blind at night.”

Can you guess who the lady was?

Find the answer here!

© Article written by Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

[1] Handwritten notes and comments made by the reader in the margins of a book.

[2] A cult of personality is the glorification of an individual through the public outpouring of flattery, praise and devotion by their supporters. A contemporary of literary giants Jonathan Swift, Alexander Pope and Samuel Johnson, and close friend of the writer and politician Horace Walpole, the poet Thomas Gray (1716–1771) didn’t in fact write a great deal of poetry, publishing less than a thousand lines of verse in his lifetime. He was, however, a prolific letter writer in an age when the personal letter was a rising art form. His correspondence to friends covered a remarkably broad range of topics with a clarity and ease not seen in his poems, a lack for which he was criticised by his peers. (Sources: enotes.com and poetryfoundation.org).

Previous post: a battle of books in Rev. James Bickham’s library

See also: University of Nottingham’s Manuscripts and Special Collections digital gallery of 114 images from Loughborough Parish Library