Loughborough Parish Library (4): a battle of books in Rev. James Bickham’s library

4 August 2023

In the latest article about Rev. Bickham and his vast collection of books which became the Loughborough Parish Library, Ursula Ackrill discusses the influence of the Puritan Hastings family on worship and education in Leicestershire from the 1500s onwards, the 18th century debate over a curriculum of Latin and the Classics versus ‘new’ practical subjects such as science and mechanics, how that played out in our local Grammar Schools and how Bickham’s own book choices act as clues to where he himself stood on the matter.

Until November 1775, people attending church services at All Saints, Loughborough, could rest their eyes on mural artworks including painted coats of arms, Old Father Time and “the figures of Moses and Aaron supporting the two tables of the Ten Commandment”. Moses and Aaron stood near the door of the North wall of the chancel. The historian John Nichols notes they were “handsomely executed in water colours” (Nichols, page 899).

On the wall above the arched entrance leading from the nave into the chancel were the King’s arms, painted in 1650, in the reign of King William III. Lastly, beside the royal arms were the arms and crest of the earls of Huntingdon – perhaps from the time of the Reformation, when the third Earl of Huntingdon had been patron of the living, between 1575-1585 (Nichols, page 899). The patronage of a living, also called advowson, consisted in the power to appoint a clergyman as priest of a parish and thus to give him the “living”, meaning the right to live off income from the parish. As receiver of parish income a priest was, and sometime still is, called the “incumbent”.[i]

The third Earl, Henry Hastings (1535-1595) had advowson of several livings beside Loughborough. Being a puritan, he involved himself in the war of ideas in his time. He used this right strategically to make political appointments, by giving the living of St Helen’s at Ashby-de-la Zouch, for instance, to puritan intellectuals such as Anthony Gilby, one of the translators of the Geneva Bible, and to Arthur Hildersham, a radical inspirational preacher and author. Allied with likeminded people, the Earl was fighting to win the hearts and minds of a society reeling from the rupture with the Catholic Church.

It has been noted by historians that the Earl may have been campaigning for more than just ideas, maybe rivalling Elizabeth I for the crown. Certainly, his lineage placed him in a plausible place for succession. However, the Earl’s record of founding and funding institutions of learning, such as the Ashby Grammar School in 1567, and the library at St Martin’s Church, Leicester, by 1586,[ii] to name just two examples beside the political appointments of rectors to St Helen’s, show a dab hand at ensuring that his puritanical goals were realised in his charities. They consumed his energy and much of his income. It is no surprise that the third Earl parted with his right of advowson of Loughborough’s All Saints only under pressure from the Queen. Nichols notes:

“When Sir Walter Mildmay had founded Emmanuel College [Cambridge], in 1584, he requested the queen, to whom he was chancellor of the Exchequer, to endow it with some ecclesiastical presentment; and, at her request, the said earl, by deed, dated Jan. 19, 1584-5, settled upon the college the advowson of Loughborough, together with those of Aller and North Cadbury, co. Somerset.” (page 899)

There was a later last-ditch attempt by the fifth Earl of Huntingdon to take back this right in 1642. By then the fifth Earl was nearing the end of his life; he had one more year to live. He claimed the transfer of advowson to Emmanuel College by the third Earl to be invalid because the Earl had overreached his authority, lacking the power to sell or give the advowson of Loughborough from the manor in the first place (Baker, page 82). If by implication he, the claimant, should have been consulted, as descendants ought to be before big decisions are made, this is quite funny. The Bishop waved the fifth Earl’s claim away.

Whilst the Earls lost advowson of Loughborough to Emmanuel College, they held on to that of Ashby – among other, smaller livings. In Ashby, puritanism drove the parish priest’s work well into the 17th century. The Grammar School’s schoolmasters built on the links established by the third Earl with Emmanuel College, by endeavouring to prepare boys for acceptance at that college. Looking back, a nice circuit emerges between Ashby Grammar School sending boys to study at Emmanuel College and then benefiting reputationally from their success. Moreover, because the prospect of obtaining the living of a parish nearby would have felt tangible to Grammar School boys inclined to study Divinity at Emmanuel College, we note that the school threw its support behind several poor pupils of merit (Fox, pages 17-30). This created a thriving environment for the life of the mind:

- John Hall (1574-1656), son of one of the third Earl’s bailiffs, would go to Emmanuel and become a Bishop as well as a published author of literature.

- John Bainbridge (1582-1643) became a famous physician, and later a professor of astronomy at Oxford. Newly graduated from Emmanuel, he returned home for a few years, set up as a physician and kept a school, whilst continuing to study astronomy. Little is known about his father, Robert Bainbridge, however a Robert Bainbridge is mentioned in the Ashby-de-la-Zouch school accounts as being the rent collector for the school-land rents; he may have been John Bainbridge’s grandfather (Fox, pages 132ff.).

- William Lilly (1602-1681), the son of a yeoman farmer, made his name as the master astrologer who predicted the execution of King Charles I. Lilly is now appreciated even more for his autobiography in which he memorialised his Grammar School days in Ashby.

The legacy of Puritanism chimed with the Grammar School curriculum. Essentially, the study of Latin and Greek was pursued to reconnect with the origins of the gospels, and so to recover the authenticity which the Apostles had lived in the beginning of Christianity – before the centuries of Catholicism when only clergy and educated, wealthy people could read the (Latin) Bible. On a practical note, Latin was Europe’s standard language in which all documents of consequence, from legal papers to dissertations, were written. It was the touchstone of the professions.

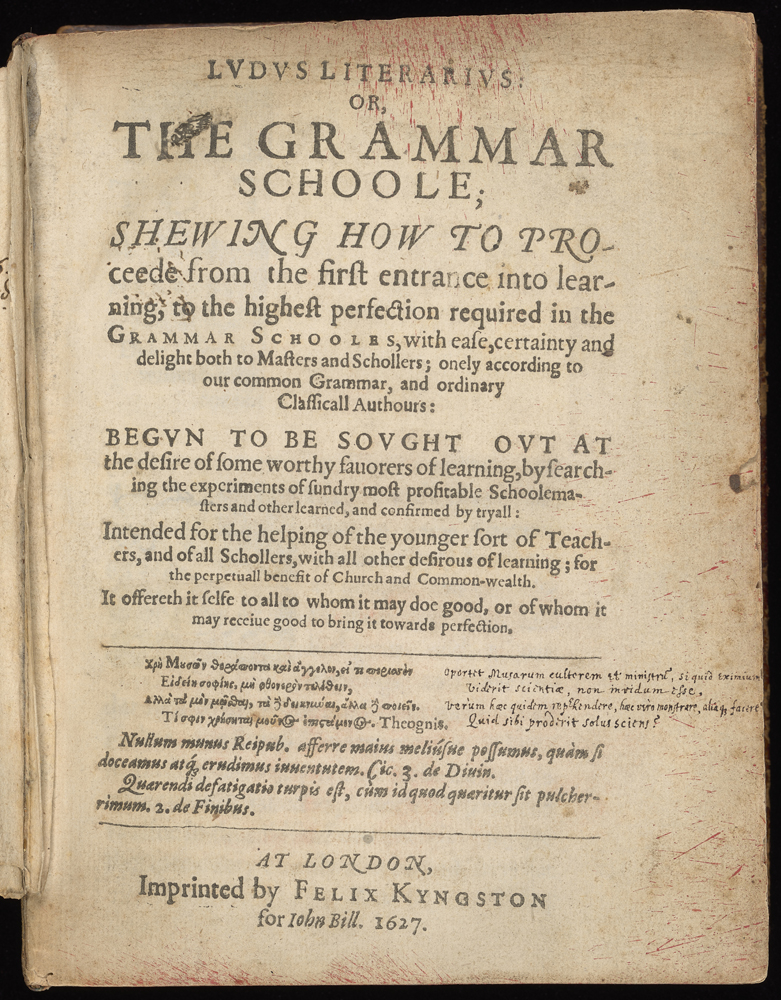

In the 17th century Ashby Grammar School had, moreover, the good fortune to appoint John Brinsley (fl. 1581–1624) as schoolmaster, who turned out to be one of the nation’s best educationalists. James Bickham owned a first edition of his 1627 work Ludus Literarius, and from the state of it we can tell that it has been well-used. Brinsley’s teaching popularised an intuitive learning method, using fun, games and schoolboys’ conversation, but implying that knowing Latin was fundamental. Brinsley may be the reason why Latin was taught in schools long after it stopped being needed.

In 1650 English replaced Latin as the official language in Britain, during the Protectorate, by a statute of 22 November 1650. However, as the Loughborough Parish Library shows, that did not mark the end of Latin, by far. 114 books in Latin survive in the LPL, but, of these, more than half (77) were published in the 18th century. In 1660, exactly ten years after English officially replaced Latin, the Royal Society was founded in London, setting standards for the pursuit of science nationwide.

The LPL shows high receptiveness towards scientific knowledge. Among the Rev. Bickham’s science books we find Isaac Newton’s new books on optics and mechanics; books with plates showing how to plot the orbit of planets and satellites; books about the use of globes for navigation; and a medicine book with anatomical illustrations. Of course, those books came with the territory when the territory was Cambridge or Oxford or London. Everywhere else in 18th century rural England, confidence in Grammar School education was at a low ebb.

During Rev. Bickham’s time as Rector, Loughborough Grammar School was stuck in a deep crisis. From its beginning the School had measured success by the number of its pupils accepted to study at Cambridge: that number sank drastically in the 18th century. To make matters worse, a schoolmaster who had been in post for 25 years neglected his work up to the point that his pupils charged him with dereliction of duty in front of the town estate (23 November 1770; White, page 129). Bafflingly, he managed to stay in post for another three years after that. Why was education in the 18th century so heavy-footed in the face of change? Why were schoolboys still “making Latins” instead of learning maths and geography?

In All Saints Church the Huntingdon arms were whitewashed over forever in 1775. Nichols writes:

“Nov. 4 1775, the king’s arms were fresh painted and finished for the church by Bagnall; at which time Moses and Aaron were washed out, as well as Time and the Huntingdon arms, by order of Mr. Archdeacon Bickham; the church new white-washed; and the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed, and Ten Commandments written in gold letters on the altar.” (Nichols, page 899).

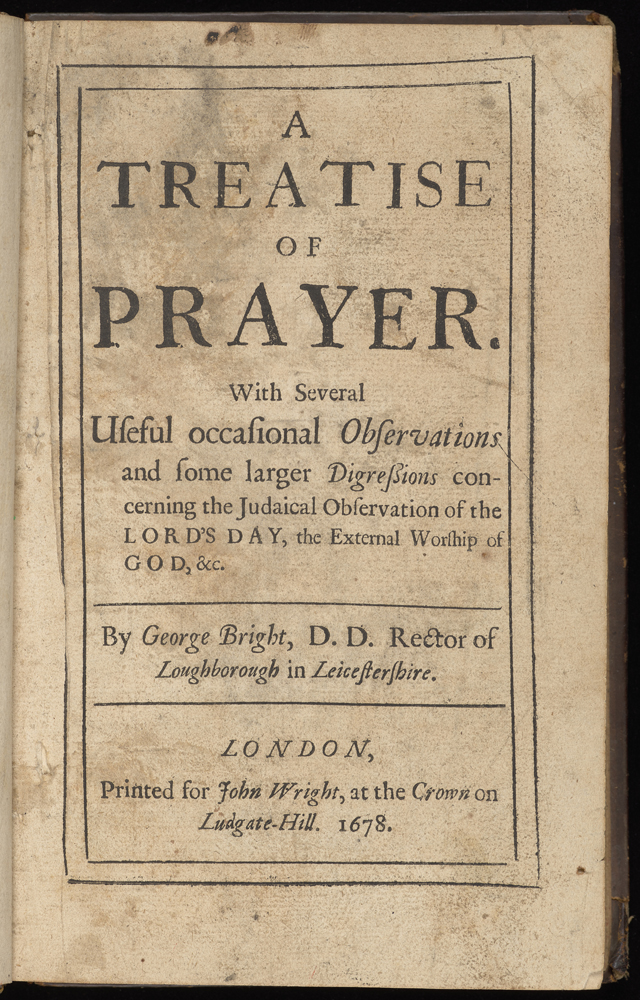

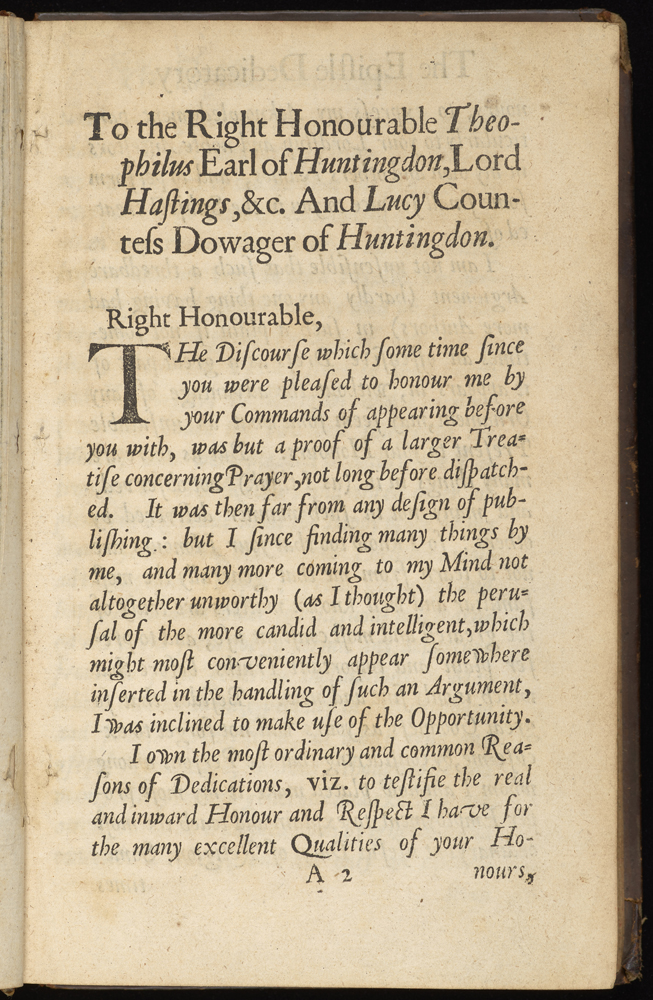

In his capacity as Archdeacon of Leicestershire, James Bickham ordered whitewashing, among all sorts of repairs and purchases, for more than half of a total of 240 Leicestershire churches during official visitations he undertook between 1773 and 1779 (Pemberton, page 56). It should come as no surprise that the Huntingdon arms were deleted from the wall in All Saints: unlike the royal arms, they were not officially prescribed. Besides, the Hastings family’s leadership was by then confined to local history. Even a century earlier, when George Bright, Rector at All Saints between 1669-1696, dedicated his 1678 book A Treatise of Prayer to the seventh Earl of Huntingdon and his mother, the Countess Dowager[iii], one cannot escape the impression that Bright’s dedication already courted the Earl and the Countess just for their cultural status as fellow-intellectuals, whilst little remained of the feudal power they had wielded in the 1500s.

However, the black maunch in the Huntingdon coat of arms has a haunting resemblance to the article of clothing which Bickham ordered – obsessively, it seems, – in his visitation records to be worn by priests. That article of clothing is a “black silk hood”, to be worn by the priest officiating service: there are 135 such items ordered. We have to ask, what accounts for the great number of mentions of “black silk hood” in relation to the overall number of vicars serving God in Leicestershire? This hood must have been important to Bickham! Why? Wearing a black silk hood over the surplice signified that the priest was a graduate of a university. At a time when school learning was in deep crisis, Bickham was signalling that degrees were valuable and conferred authority. Priests should be proud to hold a degree and wear the hood at holy services.

Kitting out priests with black silk hoods might seem like a rather quaint or hopeless gesture when we look at the hold which the old ways, symbolised by the maunch in the Huntingdon coat of arms, still had over a society beginning to modernise. The Reformation had not just enshrined the study of the classics in schoolrooms and turned religion into an open door to the past, where every Protestant could encounter Christ as directly as His disciples did in Galilee, A.D. The books collected by our Rev. Bickham in his library show us that classical antiquity, the Greco-Roman stories, had crept into popular imagination.

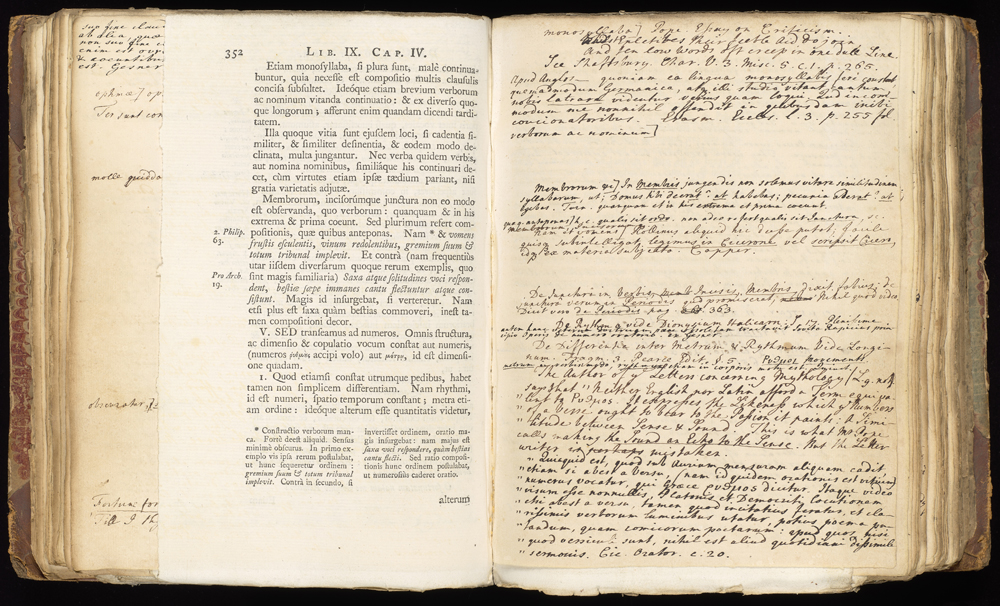

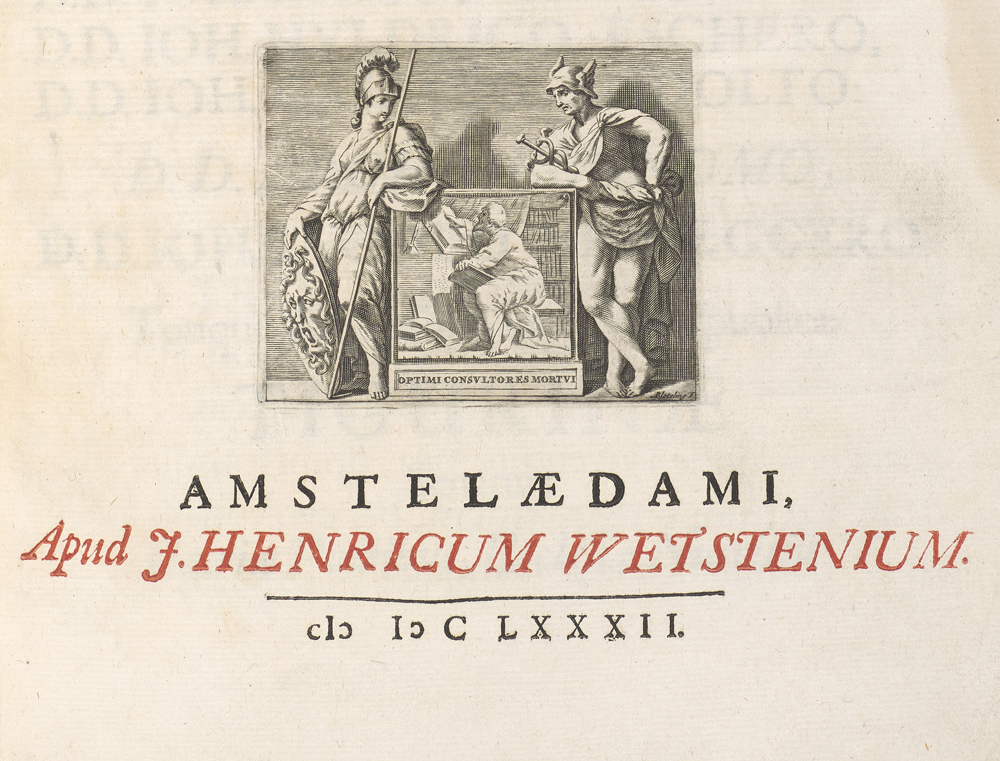

Publishers from London and cities across continental Europe published Latin as well as modern language books and sold them across national borders, as evidenced by the fact they were gathered in collections like Rev. Bickham’s. These publishers designed brand signs, the so-called printer’s device, which were engraved on every title page’s lower bottom half, with figures from the classical ancient world. The ancients were aspirational glamour figures, used to signify quality and guarantee value for money.

Writing of the mentality of medieval western Europe, Simon Winder notes that: “Humans were doubly fallen though – not just expelled from Eden, but also expelled from the classical ancient world. The medieval rulers of Western Europe were obsessed by a sense that they too were the mere followers of ancient greatness. Their battle tents and palaces were festooned with huge tapestry images of Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great.” (Winder, page 33)

What we notice looking through the books of Rev. Bickham is that by the 18th century the ancients were popular culture, referenced to enhance prestige as readily as today’s celebrities are in product endorsement. And yet, at some point in becoming a modern capitalist society in the 18th century, the reflex to look back across millennia for truth and authenticity, to the beginning of our Judeo-Christian and Greco-Roman history, was replaced with the belief that humanity has what it takes to progress to better things – in future. That our golden age was yet to come.

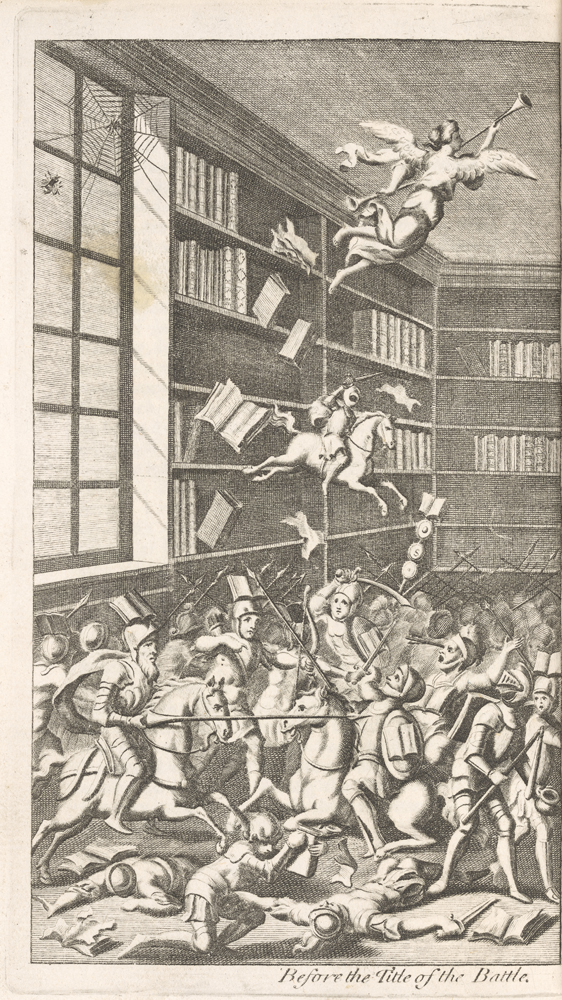

A curious little story in Rev. Bickham’s library tells us more about the missing step between the two mindsets. It was written in 1704 by Johnathan Swift, author of Gulliver’s Travels. Swift’s politics were Tory, but it is simplistic to expect his sympathies in An account of a Battel between the Ancient and Modern books in St James’s Library to be with the Ancient books. The story introduces the concept of the original thinking mind, which has enough native ingenuity and talent to originate inventions that improve and ultimately outdo legacy practices.

The originator of inventions is voiced in this story by the spider, whose net is torn by a roaming bee. Their confrontation takes place by a window of St James’s Library where the books face each other in battle: the Ancients being authors from antiquity and their contemporary champions, the Moderns on the other hand being a motley crew of critics – because change requires critique – and assorted contemporary innovators, especially in the fields of mathematics and architecture. In those disciplines the Moderns felt they had the advantage over the Ancients.

Whilst the Battle carries on, the spider and the bee engage in their debate. Swift seems to be on the side of the bee, however the spider has arguably the sharper-written lines. The spider disses the bee for being “but a Vagabond without House and Home, without Stock or Inheritance […] born to no possession of your own […]. Your livelihood is a universal Plunder upon nature; a Freebooter over Fields and Gardens;” (Swift, page 170). His accusation against culture derived from widespread sources recalls a more recent incarnation of this idea, expressed by Teresa May at the Tory Party Conference 2016: “If You Believe You are a Citizen of the World, You are a Citizen of Nowhere.”

As for himself, the spider says: “I am a domestic Animal, furnish’d with a native Stock within myself. This large Castle (to shew my Improvements in the Mathematicks) is all built with my own Hands, and the Materials extracted altogether out of my own Person.” (Swift, page 170) However, the large castle is in fact a spider’s net which the bee tore to pieces without even meaning to. Swift thus makes the argument that the inventions of the Moderns cannot last. In this staged debate Swift allows the bee to win. History was on the side of the spider, as Swift surely knew. It was the spider’s confidence in his own genius that was lacking in Bickham’s contemporaries who failed so miserably to rethink education.

Better schools were not unheard of, but without a national overhaul they could not prevail. A private school, the Loughborough Academy, sprang up in competition with the old Grammar School in 1793, opening in a house on Derby Road. It taught the old Grammar School subjects of Latin, Greek and grammar alongside “French, Italian, writing, arithmetic, astronomy, geometry, navigation, merchants’ accounts, mensuration (ie measurement) of superficies and solids, surveying, gauging, mapping, architecture, geography, use of globes, projection of the sphere, drawing, dancing and fencing.” (White, 130) Had Bickham still lived, he would have approved.

© Article written by Manuscripts and Special Collections, University of Nottingham

Resources:

John Nichols, The history and antiquities of the county of Leicester : Compiled from the best and most antient historians, Volume III, Part II (1795-1815)

Thomas North, The Accounts of the Churchwardens of St Martin’s Leicester, 1489-1844 (1844)

M. Claire Cross, The Third Earl of Huntingdon and Elizabethan Leicestershire, in Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 36 (1960)

Margaret Baker, The life and times of the Rectors of Loughborough (2012)

Levi Fox, A Country Grammar School (1967)

Alfred White, A history of Loughborough endowed schools (1969)

Visitation by Archdeacon James Bickham, 1775-1779, pp. 1-296. In Leicestershire Record Office, Document Reference 1D41/18/21

W.A. Pemberton, The parochial visitation of James Bickham D.D. Archdeacon of Leicester in the years 1773 to 1779, in Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 59 (1984-85)

Simon Winder, Lotharingia : a personal history of France, Germany and the countries in between (2019)

Jonathan Swift, A tale of a tub : Written for the universal improvement of mankind. To which is added, an account of a battle between the ancient and modern books in St. James’s Library. The 10th edition. (1743)

[i] Back then the parish priest’s income came directly from nearby land: glebe income and tithes. Glebe is an area of land within a parish used to support a parish priest. A tithe is the tenth part, the amount each parishioner had to contribute from their own income for the maintenance of the priest. Tithe payments hark back to early Christianity, adapted from the Old Testament: Every tithe of the land, whether of the seed of the land or of the fruit of the trees, is the Lord’s; it is holy to the Lord. (Leviticus 27:30-34).

[ii] The library commissioned by the third Earl formed the nucleus for the Leicester town library, which moved to the Town Hall in 1635, according to M. Claire Cross (Cross, page 15 and North, page 132). The surviving St Martin’s books are now kept in display cabinets in the Guildhall.

[iii] Lucy Davies Hastings, Countess Huntingdon, wrote poetry, or has poetry attributed to her as she never published it; her writings are kept in the University of Edinburgh (MS Laing III. 444).

M. Fabii Quintiliani Institutionum oratoriarum. Volume 2. Loughborough Parish Library, PA6649.A2 .D38, barcode: 1008347058

Previous post: Loughborough Parish Library (3): curator James Bickham (1719-1785)

Next post: Loughborough Parish Library (5): A What-if story from Loughborough’s Old Rectory